WELCOME TO

GREEN WALK, STANDISH

“…Located within the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.”

Green Walk is set in 32 acres of beautiful historical landscape, featuring aboretum trees and established gardens.

There are far-reaching views across the Severn Valley to the Forest of Dean hills and beyond.

At various points of interest around the estate you will find these information boards which we hope will be interesting and informative and add to your enjoyment and overall experience of this exceptional development.

The estate is first recorded by name as early as 1582.

Since then, it has gone through several transformations, from a hunting lodge for the nobility to a hospital serving First World War soldiers and, later, the population of Gloucestershire.

It has played a major role in the lives of local people for much of the 20th century and is now home to a new community of residents, who are enjoying the benefits of living in this beautiful parkland environment.

THE SPRING POND

…Developed in the 1860’s, the pond is vital to the diverse ecology to be found on the estate.”

In winter, they hibernate in pond mud or under log piles.

Male common frogs have ‘nuptial pads’ on their front feet to help them grip on to females during the breeding season.

A female frog may lay up to 4,000 eggs in one spring! Spawning as early as December or as late as April depending on the weather.

After hatching, tadpoles take about 14 weeks to metamorphose into froglets.

The common toad has a rough skin compared to the smooth skin of the common frog, and it crawls rather than hops.

They hibernate over winter, often under log piles, stones or even in old flowerpots and then migrate back to their breeding ponds on the first warm, damp evenings of the year.

Female toads lay their spawn in long strings around aquatic plants, with two rows of eggs per string.

They hibernate underground, among tree roots and in old walls.

Smooth Newts eat insects, caterpillars, worms and slugs while on land, and crustaceans, molluscs and tadpoles when in the water.

They are most active during the night.

These large colourful insects have superb all-round vision for hunting their flying insect prey, but are easily spooked – stand stock-still and you will often see them return to the same stem perch or resume their regular patrol up and down the hedgerow or stream bank.

Dragon and damselflies live in a variety of wetland habitats, but always favouring those with good water quality, as their nymphs grow underwater and require clear water in order to hunt.

Water Boatmen live in water. They have long hind legs, covered in hairs, that they use like paddles to swim. Their middle legs are slightly shorter, but their front legs are very short and are used to scoop up food.

They spend most of their time at the bottom of the pond, coming to the surface only to renew their air supply.

They eat plant debris and algae.

Males attract females with a ‘courtship song’, produce by rubbing their front legs

In the 1860s, Richard Potter developed the land and gardens of Standish House in Victorian style.

He built heated greenhouses to provide the household with year round produce and planted watercress beds.

He also built the brick dam which enabled the pond to be created.

Beneath the dam was an ice house where ice could be

collected from the pond in the winter and stored for use in the house.

Later, when the House became a hospital, patients and visitors were able to enjoy the benefits of a stroll around the pond.

One local resident remembers forgetting to put the brakes on her husband’s wheelchair and almost rolling him into it!

THE BIRDS OF GREEN WALK

Standish House & estate is home to a wide variety of bird species.

Bird-boxes have been installed around the site to provide them with safe habitats.

They are mottled brown in colour, with light streaks and white underparts.

They have a white stripe above the eye and a long, thin beak which curves downwards.

Their stiff tail is used like an extra limb to help brace against vertical trunks.

Their brown feathers help them to easily blend in with the trees they climb.

Goldcrests are named after the crest of bright feathers in the middle of their head.

Nesting usually starts in April, and the female will lay a clutch of six to eight eggs.

The nest is rounded in shape and is delicately built in a tree using spiders’ webs, moss and lichen.

The “Ter whitt Ter woo” call is actually the female calling ‘ke-wick’ and the male answering with a wavering ‘hoohoo’.

They can often be seen and heard in mature trees.

It has a very distinctive bouncing flight and spends most of its time clinging to tree trunks and branches, often trying to hide on the side of the tree away from the observer.

Its presence is often announced by its loud call or by its distinctive spring ‘drumming’ display.

The male has a distinctive red patch on the back of the head and young birds have a red crown.

Its screaming call usually lets you know a jay is nearby and it is usually given when a bird is on the move, so watch for a bird flying between the trees with its distinctive flash of white on the rump.

Jays are famous for their acorn feeding habits and in the autumn you may see them burying acorns for retrieving later in the winter.

Buzzards are large birds with broad rounded wings and short tails.

They are typically brown with white undersides to the wings.

A Buzzard’s beak is sharp and hooked and it has large feet with sharp talons.

It has a wingspan of around 120cm and weighs up to 1kg.

Buzzards feed mainly on rodents such as voles and mice, however they can also take prey as large as rabbits or as small as earthworms.

They are similar in size to a sparrow.

The species is a favoured host for the Cuckoo, which often lays its eggs in the Dunnock’s nest. Once hatched, the cuckoo chick will push any Dunnock eggs and chicks out of the nest, ensuring it receives the full attention of its surrogate parents, who will continue to feed it as if it were their own offspring.

Look for flocks flitting from branch to branch, rarely staying still for more than a second.

The long tail is the easiest way to distinguish the species from other small birds. Its call is a high-pitched ‘tsurp’ sound.

They feed mainly on insects and invertebrates. The eggs of moths and butterflies are commonly taken, as are caterpillars.

THE BAT HOUSE

“The Ritz of all Bat Houses”

Take a walk around dusk on a summer evening and there is a good chance you’ll spot bats flying above, especially if you are close to water as that is where many insects may be found.

All UK bats are nocturnal, feeding on midges, moths, crane flies and other flying insects that they can find in the dark by using echolocation.

They hibernate over winter, usually between November and April.

In the 1860s Richard Potter built a dam to create the pond at Standish House. Beneath the dam was an ice house where ice could be collected from the pond in the winter and stored for use in the house.

During recent ecological studies, Lesser Horseshoe bats were found to be living in the ice house.

Bats are fascinating animals – the only flying mammal.

There are over 1,400 species of bats in the world, and more are still being discovered. We are lucky enough to have 18 species of bat in the UK.

All species of bat in the UK are protected by law due to the dramatic decline in their numbers. This is the result of the loss of feeding habitats & their insects, and flight lines, with development affecting roosts. It is therefore illegal to disturb, injure or kill them.

The Standish House Bat House has been built beside the pond and has been carefully designed to provide shelter for the many different types of bat that live in this area.

Working closely with the Natural England Organisation, the Bat House P J Livesey have built here is the very best design in re-housing: It is roughly 1,000ft sq. – ‘comparable to a typical 3-bed family home!’

They hunt close to the ground, rarely more than five metres high and often snatch their prey off stones and branches.

Unlike other bat species, Horseshoe bats are able to wiggle their ears, and those of Lesser Horseshoe bats are particularly mobile, helping them to locate the precise position of prey.

When resting, it rolls its ears back or hides them underneath its wings.

It is a medium-sized bat, growing to around 8cm in length, including ears.

It has light grey-brown fur and a pale underside.

They usually follow linear features like streams, fences and hedges, and fly a bit slower than other bats.

Natterer’s bats are found in deciduous woodland and parkland, particularly

areas close to water.

These bats are very quiet, so chances of hearing them are slim; however, they do have a slow to medium flight so you might just catch a glimpse of their white belly as they fly overhead.

They make extensive use of buildings and are thought to roost in them almost all year round.

Serotines can often be heard squeaking loudly just before they emerge at dusk.

They generally feed in woodland habitats and their long, broad wings enable them to manoeuvre skilfully amongst the trees and to dive quickly to catch flying insects.

They also feed around street lamps or snatch insects from leaves or the ground.

Noctule bats are high flyers, flying above the tree canopy, so keep your eyes to the sky to catch sight of one.

They particularly enjoy eating flying beetles, such as the large cockchafer.

Despite being the UK’s largest bat, the Noctule could still fit in the palm of your hand.

WOODLAND WALK

Enjoy a stroll through our Woodland Walk and see a number of key landscape and historical water features retained for their importance in establishing a valuable and diverse ecological enviroment.

The most venerable tree within this very special area is the incredible, hollow, English oak you can see here.

Standing approximately 15 metres high, with a huge girth of 3 metres, it dominates this area and is well over 300 years old. You can only imagine the people and lives it has witnessed in all that time!

As trees reach old-age, they naturally decay and hollow from within, as you can see here.

Unfortunately due to vandalism, in order to protect it from further damage, it has now been boarded up.

Perhaps the eagle-eyed amongst you will spot the ‘Oak Leaf’ shaped boards that the groundsman inserted?

Also to be found within the ‘Woodland Walk’ are the remains of the water irrigation system and ornamental fountain installed in the mid-1800s by long-standing tenant of Standish House, Richard Potter.

In order to irrigate the grounds, Potter and his landscaper devised a clever system that used the natural flowing spring on the site and diverted the water via a system of tunnels and piping using gravity as its force.

This not only provided a constant natural flow of water into the pond, but also powered the fountain and came up in various areas on the land, to water valuable trees, plants and vegetation, before finding an outlet futher down into a natural stream.

In the spring, this whole area is carpeted with wild garlic, the scent which fills the air with a delicious aroma!

A beautiful Veteran Yew also stands within the Woodland Walk.

Yews were often found in churchyards (as a precaution to avoid livestock grazing on their harmful leaves), and therefore many myths have grown up around them throughout history. This is largely due to their ability to regenerate, producing fresh shoots from apparently ‘dead wood’, such as beams within buidlings or the staffs of holy men.

In many trees the rings cannot be counted, or carbon dating undertaken, as their ancient hearts rot and disappear, but it is widely accepted that some Yews in Britain could be as much as 2000 years old.

MAJESTIC TREES

As you stroll around the grounds, the most notable trees that you will see – in addition to the veteran pedunculate oak and yew trees described on the ‘Woodland Walk’ information board – are listed below.

See how many you can spot!

It has been created in cultivation with the Common beech. Introduced into England in the early 1800s – hence its installation by the Potters – it has remained a favourite speciment tree ever since.

Fagus sylvatica ‘Pendula’ – also known as Weeping beech.

This is a slow growing tree, with a sweeping, drooping habit.

The beautiful specimen at Green Walk is approximately 13 metres high.

Lucombe oak – A hybrid of the Turkey oak and Cork oak. This is a botanically remarkable tree. It has distinctive cork like bark and can grow incredibly large, at an incredible rate.

They were first grown by William Lucombe in 1762, when he discerned that the saplings of the Turkey and Cork oaks

retained their leaves in the winter and he began to experiment with cloning the two specimens in his plant nursery. In fact, Lucombe was so proud of his creation that he decided to have his coffin made from the wood of one of them. He had it made in what he considered to be good time, except that he actually lived until he was 102 years old and the original coffin had rotted by the time of his death, requiring a further Lucombe oak to be felled and a new coffin made!

A true Lucombe oak must be taken as a clone from the parent plant, as the acorns will produce a hybrid.

Quick Facts

Leaves; Dark green and variable in shape – some lobes are elaborate and pointed whilst other leaves have rounded, simple lobes. To touch they are rough and thick, shiny above but felted underneath.

Fruits; The large acorns mature 18 months after pollination. Acorns are quite distinct – orange at the base, graduating to a green-brown tip, and with a ‘hairy’ acorn ‘cup’, which looks like a hat made of moss.

Liriodendron tulipifera – also known as the ‘Tulip tree’.

There is a particulary fine example of this tree on the grounds.

It is well formed and stands at 20 metres high. It is often known as the Tuliptree, due to the distinctive yellow and green tulip shaped flowers it produces in June-July on older trees.

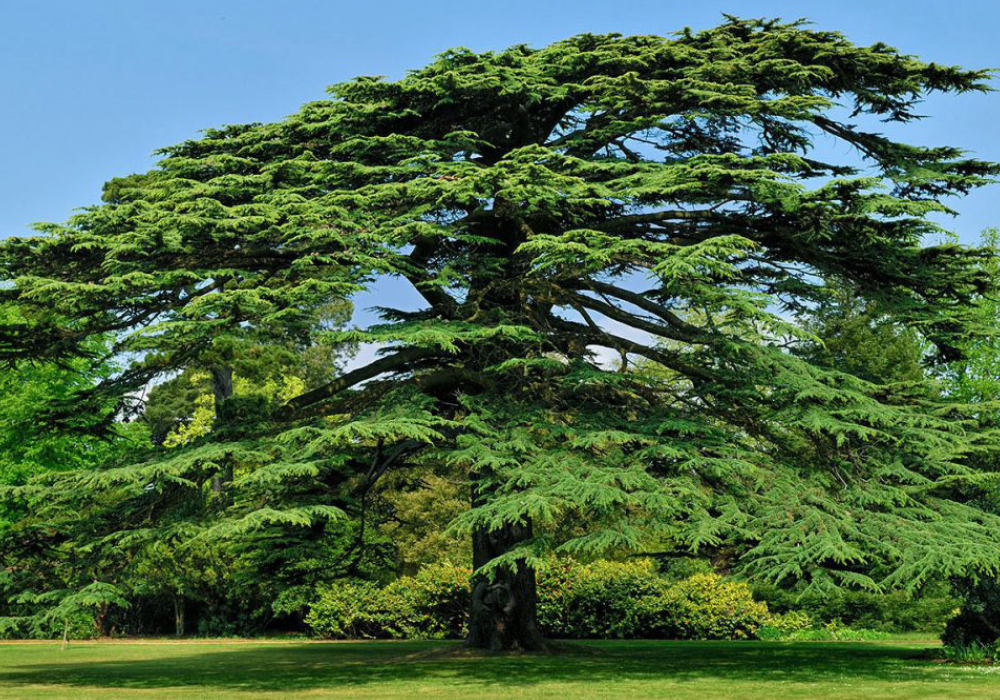

Cedrus libani – Cedar of Lebanon (Native to Lebanon, and the central emblem of their national flag).

In the UK you’ll find it planted in the grounds of large estates and parks. At Green Walk we have a particularly fine example, which stands at approx. 24 feet tall and has a girth of 1.8 metres.

Cedar trees provide habitats for many animals and invertebrates because as they age their trunks and branches create cracks and crevices which act as nesting places for, amongst other things, owls and bats. Cedar-oil was used by the Romans for the protection of their manuscripts.

“There are … some notably large veteran trees and uncommon species (in the area). These are excellent examples with some dating back to the original parkland landscape of the eighteenth century and so are both historically and visually important features”

During their 30 year tenure of Standish House, the Potter family (typically for wealthy landowners/tenants of this period) undertook major landscaping works on the estate. As part of this work, they supplemented the veteran trees already standing in the grounds with a number of ‘fine and uncommon specimens’ *.

Their overall scheme created significant and romantic informal parkland and gardens for their own enjoyment – and also to impress their friends and visitors! Landscape features that remain today include the grass tennis court, lake, formal round pond, walled gardens, paths and, most especially, a large number of remarkable and unusual trees. Many of these are highly notable trees locally and a small number nationally.

The most outstanding of the trees is a large Cork oak which is considered to be one of the largest, if not the largest example of this species in the country.

Our beautiful Cork oak is by far the most exceptional tree on the estate – so much so, it has been given its very own information board. The board can be found on the land adjacent to it, named the ‘The Cork Tree’.

THE CORK OAK

“…Its shrunk! But still the best in England.”

The magnificent Standish Cork Oak tree is one of the oldest in Britain – and the largest! It boasts a girth of over 5 metres, and a height of approx 18 metres!

In 1992 its height was measured at 21 metres – so it’s actually shrunk!

The cork oak is an evergreen tree, of the Fagaceae family (Quercus suber), to which the chestnut and oak tree also belong. There are 465 species of Quercus, mainly found in temperate and subtropical regions of Southwestern Europe (e.g. Portugal and Italy) and Northern Africa (e.g. Morocco & Tunisia). Cork is harvested from the Quercus suber L species.

Q Which is the largest and oldest cork oak in the world?

The oldest and most productive cork oak in the world is the Whistler Tree, in Águas de Moura, in the Alentejo region (South of Portugal).

The cork oak was planted in 1783, stands over 14 metres tall and the diameter of its trunk is 4.15 metres.

Its name comes from the noise made by the numerous songbirds that shelter among its branches.

Since 1820, it has been harvested over twenty times.

Its 1991 harvest produced 1200 kg of cork, more than most cork oaks yield in a lifetime. This single harvest produced over one hundred thousand cork stoppers.

Q What is stripping?

Stripping is the ancient process of extracting the bark of the cork oak – the cork.

Today, this work is still done by specialised professionals, with absolute precision, who use just a single tool: the axe.

This delicate operation takes place between May and August, when the tree is at its most active time of growth and it is easier to remove the bark from the trunk.

Q When does the first stripping take place?

The first stripping takes place when the cork oak is 25 years old and the trunk has reached a diameter of 70 centimetres, measured 1.3 metres from the ground.

Subsequent stripping takes place with an interval of at least nine years, which means that the harvesting of the cork will last 150 years, on average.

The first stripping is called “desboia” from which the virgin cork is obtained, which has a highly irregular structure and hardness that make it difficult to process. Nine years later, when the second stripping takes place, the cork, known as “secundeira”, has a regular structure which is not as hard.

The cork from these first two harvests is not fit for the manufacture of stoppers and thus used in other applications for insulation, flooring, decorative items, amongst others. From the third and following strippings the “amadia” or reproduction cork is obtained.

Only this cork has a regular structure, with a flat front and back and the ideal characteristics for the production of natural, quality cork stoppers.

Q Is the cork used immediately after being stripped from the cork oak?

No. After stripping, the planks are stacked into piles in appropriate structures and shall remain outdoors for at least six months for the cork to stabilise. This process is governed by the strict compliance of the Code of Cork Manufacturer Practices.

Q Does the cork oak need to be cut down to harvest the cork?

No. Stripping is carried out manually and the trees are never cut down. After each stripping, the cork oak undergoes an original process of self-regeneration of the bark, which gives the activity of cork harvesting a uniquely sustainable nature.

Q Besides cork, what other parts of the cork oak are used and for which purpose?

Nothing is wasted from the cork oak, all its components have a useful ecological or economic purpose:

• The acorn, which is the fruit of the cork oak, is used to propagate the species, as animal fodder and in the manufacture of cooking oils;

• The leaves are used as fodder and a natural fertiliser;

• The material from tree pruning and decrepit trees provide

firewood and charcoal;

• The tannins and natural acids contained within the wood from the tree are used in chemical and beauty products.

Q Are cork oaks ancient trees?

Yes. Some scholars argue that the existence of cork oaks dates back over 60 million years.

It has been scientifically proven that cork oaks survived the ice age in the Mediterranean Basin, over 25 million years ago. In Portugal, where the largest cork oak forest area in the world is found, a fossil fragment over ten million years old was discovered which is testament to the ancient existence of this tree in the country.

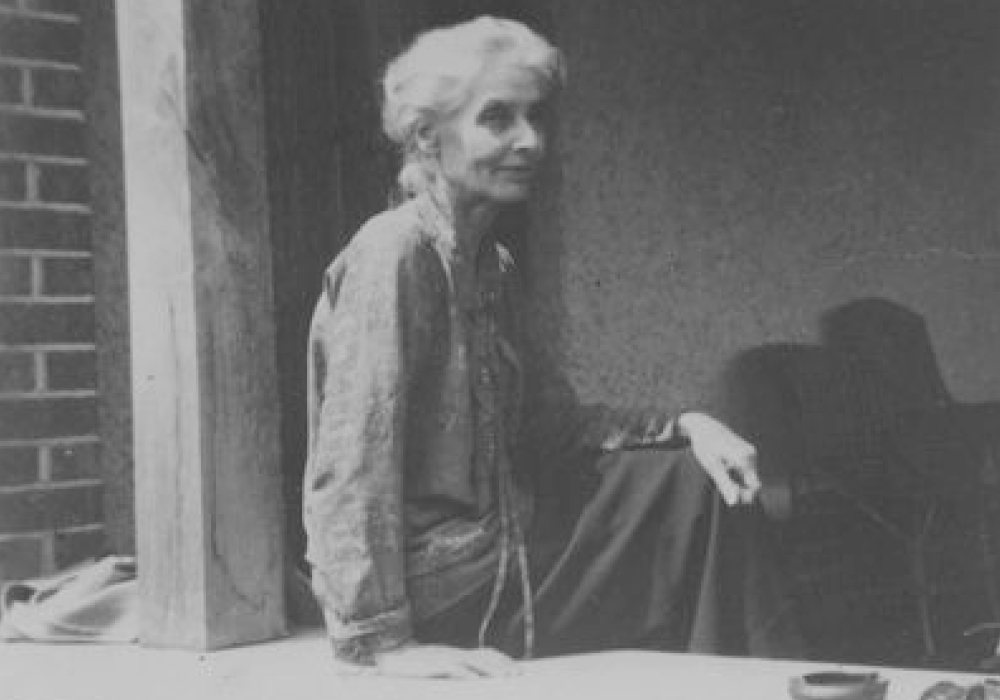

BEATRICE WEBB

…English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer, described as;

“The greatest woman of the generation” – Maynard Keynes

Early Years – Beatrice Potter was born in Standish House on the 22nd January 1858, the last but one of the nine daughters of wealthy businessman Richard Potter and his wife Laurencina Heyworth. Potter held the firm belief that women were superior to men, and all his daughters received a sound education from live-in governesses. In addition, from an early age Beatrice was self-taught and cited the Co-operative Movement and the philosopher Herbert Spencer as important influences.

In 1883 she joined the Charity Organisation Society (COS), based in Soho, London, an organisation that attempted to provide Christian help to those living in poverty.

Beatrice had a real focus on the vital need to alleviate and reduce the causes of poverty and learnt about the conditions of the poor by working amongst them.

Beatrice and Sidney Webb – Beatrice met her husband, Sidney Webb, through the Fabian Society, of which they were both early members. Attracted by Sidney’s mind and principles, theirs was a lifelong partnership of like-minded socialists and reformers.

“…It seems an extraordinary end to the once brilliant Beatrice Potter to marry an ugly little man with no social position and less means, whose only recommendation, so some may say, is a certain pushing ability. And I am not ‘’in love’ with him, not as I was. But I see something else in him (the world would say it was a proof of my love) – a fine intellect and a warm-heartedness, a power of self-subordination and self-devotion for the ‘common good’.” (Beatrice Webb, diary, 20 June 1891)

They married in 1892, spending their honeymoon carrying out research. The Webb’s worked on several books together including The History of Trade Unionism (1894) and Industrial Democracy (1897).

On the death of her father in 1892, Beatrice inherited an income of £1,000 a year. This money enabled Sidney to leave the Civil Service and go into politics, being elected to the London County Council in the same year. At that time, women did not have the vote and so could not stand for election to local councils or Parliament.

Together with George Bernard Shaw, they continued to work as prominent Fabians, Sidney writing ‘Facts for Socialists’, the first Fabian tract, and Beatrice a paper on ‘The Co-operative Movement.

In 1905, Beatrice was appointed to the Royal Commission on the Poor Law and the Relief of Distress. Her view differed from the majority of members, who proposed to maintain the underlying principles of the Poor Law.

In 1909, she was lead author of a Minority Report, setting out a radical set of proposals aimed at shifting the agenda from the relief of poverty to its prevention, recommending a “national minimum of civilised life” and putting the responsibility for the conditions that created poverty at the door of government rather than the individual.

In 1922, Sidney became a Labour MP.

William Beveridge who, in 1942, produced the Beveridge Report which founded the modern ‘cradle to grave’ welfare state, worked as a researcher on the Minority Report. Prime Minister Clement Attlee described the Minority Report as “…the seed from which later blossomed the welfare state”.

Following the Minority Report, the Webbs decided to launch a new weekly paper to spread their beliefs to a wider audience. The result was ‘The New Statesman’, 1913, which is still very much in circulation today.

Further notable books and studies written by the Webbs or by Beatrice alone include:

1919: Wages of Men and Women: Should they be equal?

1922: English Prisons

1926: My Apprenticeship

The London School of Economics – In 1895 the Webbs, together with Bernard Shaw, established The London School of Economics (LSE) on the lines of the Ecole Libre des Sciences Politique in Paris. The idea was that students should be free to study social conditions in a scientific way, pursuing the truth independent of any dogma.

Beatrice and Sidney both lectured at the LSE in its early days. William Beveridge, LSE Director (1919 – 1937), wrote: “The School of Economics is the favourite child of the Webbs” due to its “bringing about of social conditions, not by revolution or violence, but by application of reason and knowledge to human affairs.”

In addition to the books she wrote with Sidney, Beatrice left a substantial literary legacy of her own, including two volumes of autobiography and four volumes of published diaries – the first entry was made when she was fifteen, the last within weeks of her death, aged 85, in 1943.

Sidney died in 1947. Although they had agreed that their ashes should be buried at Passfield, at the suggestion of George Bernard Shaw they were re-buried in Westminster Abbey in December 1947 – the only married couple to be honoured in this way. The address was given by Prime Minister Clement Attlee, who said: “Millions are living fuller and freer lives today because of the work of Sidney and Beatrice Webb.”

STANDISH HOUSE

…A brief history

The former Standish House and Standish Hospital lie within a wider area which was once part of Standish Park, a hunting ground which presumably dates from the Middle Ages but is first recorded by name in 1582. In 1611 the park was purchased by William Dutton and family, later the Barons of Sherborne, who retained ownership until the early 20th century.

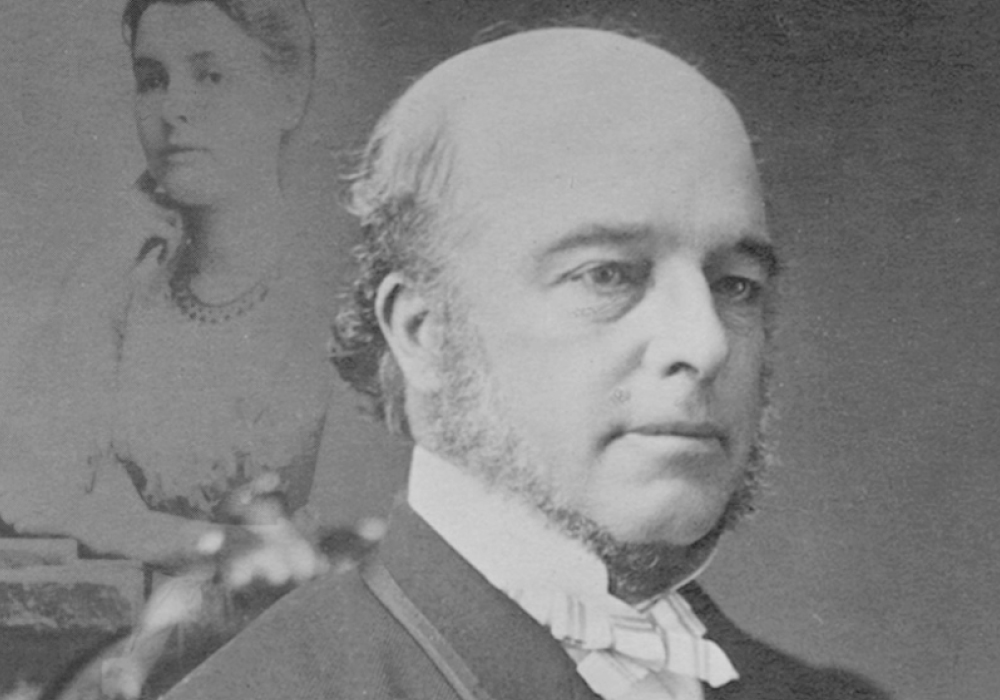

James Napper Dutton, 1st Baron Sherborne – It is believed that the 2nd Lord Sherborne built the current main house for use as either a hunting lodge or as temporary accommodation whilst his main house at Sherborne Park was being rebuilt. It is unclear how much time Lord Sherborne actually spent there – the 1841 census shows that the building’s only residents were four female servants and a glazier. Therefore in 1853 the barely-used house was leased out to the Potter family.

On his death, James Dutton’s obituary read: “Distinguished through a long and honourable life by the exercise of every generous and noble quality that could adorn the heart of man.”

The Potter family – The Potter family leased Standish House for almost thirty years, from 1853 – 1882. Richard Potter and his wife Lawrencina had a total of nine daughters, all of whom were brought up at Standish House and received an excellent education, thanks to their father’s belief that women were superior to men. In fact, the second youngest of these daughters was well-known Victorian social reformer and economist Martha Beatrice, (later known as Beatrice) born in Standish House in 1858.*

It was during the tenure of the Potters that many improvements were made to the mansion house and its grounds, to bring it up to the standard befitting the status of such a wealthy Victorian gentleman. One of the more important changes was the addition of an upper storey to the northern part of the house in 1865. The work was described by Beatrice Webb in her autobiography: ‘In 1865 it was felt by my parents that the house at Standish was hardly big enough for the large family and many guests… It was decided that my father should build another storey on part of the house; a billiard room was built over the school room and another storey over the nursery corridor.’

She goes on to give us an interesting insight into the internal use of the house itself: It was ‘sharply divided into front and back premises. The front…overlooked the flower gardens and the beautiful vale of the Severn; the stair and landings were heavily carpeted and the bedrooms and sitting rooms were plainly but substantially furnished in mahogany and leather. In this front portion of the house resided my father and mother and honoured guests’. It contained the principal rooms: the ‘best drawing room’, Lawrencina’s boudoir, library, study and the family dining room.

The back premises overlooked the servants’ yard, stables and extensive kitchen gardens. They housed the servants, housekeepers and governesses, the nurseries, the schoolroom, the one bathroom of the whole house and Richard’s billiard and smoking room. A stone-paved yard separated the kitchen, sculleries and larder from the laundries.

Richard Potter – Richard was the son of a radical non-conformist Liberal Party MP, he qualified as a lawyer and invested in a timber importing business in Gloucester. This branched out into supplying pre-fabricated wooden buildings for Australian gold miners and for the army.

The timber importing business had provided sleepers for the railway industry, which led to Potter becoming a major investor in railways in both England and Canada. He was chairman of the Great Western Railway, and also of the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada.

Mrs Potter died in 1882 and Mr Potter vacated Standish House shortly after.

The King Family – On 24 June 1884, Mrs. Annie Poole King leased Standish House on a contract term of 21 years from Edward Dutton, 4th Baron Sherborne, at a rate of £150pa. She moved in with her five children, plus a coachman, cook, housekeeper, and gardener.

Mrs. King was a member of the Berkeley Hunt and at that time the house had a stable block capable of housing her 30+ horses. It was Mrs King’s eldest daughter, Mary who was later responsible for the house becoming a hospital.

The Boer War had a major impact on the King family’s finances and they had to leave Standish House in 1897.

20th Century – The census return for 1901 shows Standish House occupied by domestic servants, with no obvious head of the household. 1911 shows the tenant as George De Lisle Bush.

In anticipation of coming war, Mary King (ex-tenant and Red Cross nurse trainer) recognised the building’s potential to be helpful in the war effort and asked Lord Sherborne to loan it for use as a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) Hospital. He agreed and Standish House and its estate began its new life as a hospital, continuing until its closure in 2004.

STANDISH HOSPITAL

“The whole hospital and site was a ‘jewel’ in a crown”. – R. White

At the outbreak of WW1, Standish House stood empty, its last tenants, the King family having moved out in 1897.

In anticipation of war, Mary King, ex-tenant and Red Cross nurse trainer, was well aware of the buildings potential to be of valuable use to the war effort. She approached its owner, Lord Sherborne and requested that the building be loaned for use as a VA Hospital.

He not only agreed but also had the house decorated, fitted with electric lights and installed additional baths and toilets, in readiness for its important new role.

An open day was held on Easter Monday, 1915, and only two days after this it received its first wounded soldiers.

The hospital had 100 beds and was staffed by 8 fully-trained nursing sisters. The rest of the staff were local volunteers from the Red Cross detachments trained by Miss King… who oversaw the running of the hospital and the training of its nurses.

She was later recognised with an O.B.E. for her work.

Life at V.A.D. Hospital – The soldiers were subject to military discipline and were expected to wear their uniforms if they were able to dress. They also helped the nurses with their chores. However, their life at Standish wasn’t too harsh – if they were well enough, they were free to leave the hospital during the day and many went into Stonehouse and Stroud – but they had to be back for 6.30pm or else they would miss supper!

Other recreational activities included painting, playing cards or even putting on plays which sometimes the nurses also took part in, as indeed they did with target practise! A great deal of time was spent outdoors, to aid recovery, and snowballing and target practise were very popular pastimes, making full use of the beautiful grounds and gardens of the hospital.

During its tenure as a WW1 V.A.D. Hospital, Standish treated 2292 casualties of war from the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and Canada.

The Sanatorium – Following WW1, the hospital was converted into a sanatorium to provide specialist care for Tuberculosis (TB) patients.

Its position, built as it is on an eminence exposed to the prevailing winds, was ideally suited for the form of treatment used to treat the condition at that time. Standish House Sanatorium was opened on 6 July 1922.

It had a total of 140 beds divided into men’s, women’s, and – due to high number of the patients being children – special children’s blocks and a playground. A school was attached to the hospital from its inception.

WW2 & Post-war years – The advent on the Second World War was again transformed Standish into a military medical facility.

Following the Allies victory, Britain began to re-build and Standish Hospital was nationalised as part of the NHS following Prime Minister Clement Atlee’s ground-breaking legislation of 1948. The hospital was taken over by the Gloucester, Stroud and the Forest Hospital Management Committee, and became a general hospital, catering largely for geriatric and pulmonary patients (1983).

It specialised in orthopaedics, rheumatology and respiratory care until it was closed in 2004.